The growth of digital technology has seen videogames play an ever-greater role as a global cultural force in our lives.

They are now recognised as the most important aspect of youth culture.[1] A recent OFCOM report stated that more 16-24 year olds play videogames than have a social media profile.[2]

Their value, both culturally and economically, came into sharp relief during the pandemic in 2020[3], with sales in the UK rising by 29%[4] on the previous year to £7bn and 62% of all UK adults playing videogames during the period[5].

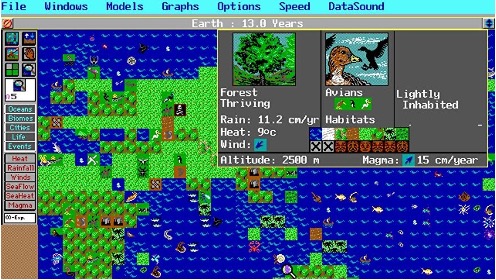

People no longer just play videogames; they also play with videogames.

Alongside the streaming of gameplay, live performance, content creation, modding[6] and cosplay[7], games have become social destinations in their own right – including to access other cultural experiences such as music concerts and film screenings.

This presents a significant and mostly untapped opportunity for public engagement.

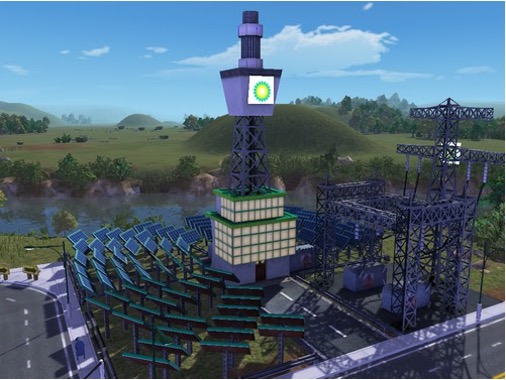

To date most engagement activities have focused on gamification[8].

However, the number of video games now available for young people to choose from has risen vastly over the last five years. ‘Steam’, the most popular PC games distribution platform saw 2964 games released in 2015, rising to 10263 in 2020[9].

As a result, investing in the creation of a single videogame as an engagement strategy can be both expensive and high risk – with any output competing with industry behemoths such as Fortnite.